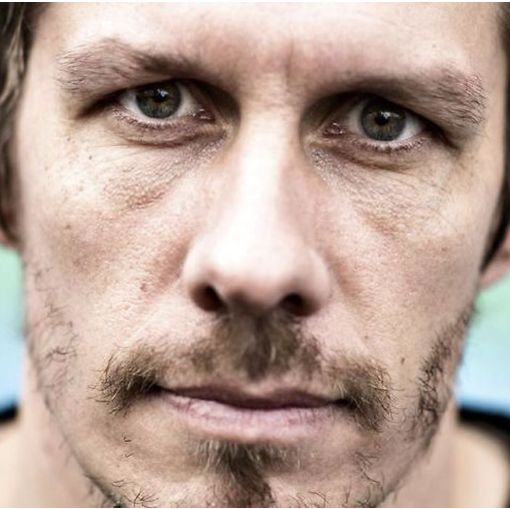

Pione Sisto’s story is, in reality, a cry for help

Published May 2020 (in Politiken):

The story about Pione Sisto – in recent time becoming very relevant once again – is unfortunately yet another example from the revered world of football about a talented player, who has lost his motivation and direction, and might never reach his full potential.

As observers of the Sisto-case, we can shrug our shoulders or shake our heads and assert that it is Pione’s own fault. And of course there is a degree of self-responsibility, and one cannot just leave their club without the permission to do so (like he did during COVID-19 in Vigo). That goes for most employer/employee relationships.

However, seen in a wider perspective, the case frustrates me, as it is not the first or the last. It is therefore about time that we within the industry evaluate ourselves and our cultures, and develop a far better groundwork for, and guidance of, the players. Earlier this spring, Manchester City player Kyle Walker also ran into problems when the British national team player first invited prostitutes to his house, despite the fact that Britain was under Covid-19 lockdown, and later went on an ‘illegal’ visit to his family.

That created a public bashing of Walker, who of course had made a bad choice, but again: where are the clubs and the sport culture when the responsibility is distributed?

Kyle Walker has been a part of the football elite environment since he was a little boy, which have shaped him as the man he is today. We have to ask ourselves how we could have helped earlier so that this would not have ended up in a negative spiral.

Pione Sisto, Emre Mor and other players gone astray is, in reality, a cry for help.

Despite the fact that players might not be aware of, or believe that they need help - they do. And only the proper kind of help that is. As it is now, players usually seek guidance from their agents, but no matter how we look at it, and despite of the competent and honest agents in the industry, it will always be an unequal relationship, as the agent bureaus only make money when the player is in the fold (often for a 2 year period of time), and primarily only when he transfers to another club. Therefore, they have an incentive to push the decisions on behalf of the player.

It resembles the situation where one buys stocks through their bank. It can be well intentioned and honest, but in the end, the bank needs to make money off of you as a costumer, and that is bound to be reflected in the guidance and recommendations. There will always be a bias.

Besides, in my experience, the agents rarely have sufficient insight and understanding to make an objective, football-based evaluation.

Said more explicitly: they have never, or rarely, been on the training field, worked with a team, or attempted to develop a player. That does not mean that an agent bureau or a counsellor cannot have value, as they both have network in the clubs, experience with negotiation and the contractual situations, and so on. I just do not believe that they can say sincerely that they always advise the players objectively.

Where are the mentors in elite sport?

It can be difficult for the players to seek out the right and objective guidance as the clubs cannot provide this either – without being biased. Very few environments give the players an opportunity to open up completely about their own problems and weaknesses, without it having consequences. A manager is likely to reconsider the spot in the starting line-up the following Sunday, if the player on Wednesday told him that he is mentally tired, demotivated, or even depressed. Again, there is a relationship which ensures an unequal conversation.

In the business world, numerous larger companies assign a mentor for younger talents. I am not to say how the distributions of roles are determined within organizations, but from the outside looking in, it appears to be much more long-term, and without the hidden agenda that either the business or the mentor has to make money off the talent at some point.

This kind of long-term, objective, and professional guidance rarely happens in the world of football. Thus, there is a need for rethinking, and developing a new mentor and counsellor role in elite football. There is a need for people with insight, experience, and football knowhow, that do not either profit from a player being sold or have the power to bench the player. The role has to remain more objective and supporting.

Players often seek support from their own family, and Sisto mentions his brother as an important ally. This is not uncommon or wrong, but I have seen a fair share of examples wherein a father, brother, uncle, or another family member takes an active interest in the career, which unfortunately very rarely enhances the value of the player, and ultimately ends up causing more harm than good.

The families are well intentioned, but exactly because of the relationship, blood ties, and the love, decisions become emotional and without proper and objective analysis. Furthermore, few family members know the industry and the details of the game from within, so they end up counselling on a matter without knowledge, and that is not counselling, but rather guessing or hoping. I can only strongly recommend that the young players do not use their family as their primary carrier advisers, because that rarely goes well, according to empirical evidence.

Meaning instead of money

And it is not just about a career path, but about the self-formation of a whole human being. What is the person’s internal drive? How shall we work to find the highest degree of purpose, and in which environments would this archetype thrive best?

Only from knowing one self and being aware of one’s own strengths and weaknesses, will a person be able to handle the challenges and changes that comes in a career. Researcher Natalia Stambulova uses the term to ‘cope’ with the different transitions, that occur in a career, and that one only can when there is balance in the players prerequisites, ‘ballast’/background/baggage, and resources. Hence, the players must be prepared better and guided in those situations and transitions, where their own families ‘ballast’/background/baggage and resources are insufficient.

In the case of Sisto, he has also become a ‘victim’ of the Instagram-generation where you have to be seen, recognized, and present yourself in the best possible way – publicly – all the time, even though the internal picture is cracking. The Celta Vigo player has plenty of confidence in his game, but when things go astray, the house of cards comes tumbling down for Pione, and that is too big a vulnerability to build an elite carrier on.

That is why analysis of the players drive is far more important than whether the next opponent plays with wide wingers on the final third, making the player a pure tactical fit. Sisto states in an interview with Danish media, Politiken (from May), quite honestly that he has all the trappings: money, a big house, a football carrier in Spain, and despite that he’s still missing the most important thing – the internal – a purpose and a feeling of happiness.

That is why we really need to go through our football culture, looking at how we can do better, develop more well-rounded and clear-minded individuals, who hold insight to their own drive and motivation, and help the young talents in finding the right advisors and mentors, who do not necessarily need to make a profit off the talent’s career. It is about time, as reflected in Sisto’s story.

The way clubs manage talent today, setting specific goals, can directly kill the passion, and the sense of purpose in the long run, if clubs and leaders are not familiar with the person’s archetype and primary drive.

Let us help the players so that we do not find ourselves with more and more unrealized talents in the future. And let’s hope Sisto finds his way back - now back home at FC Midtjylland.